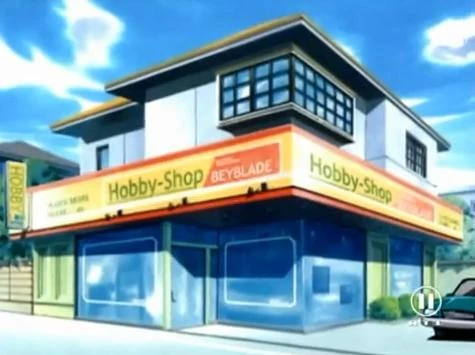

If you go back to the very first Beyblade, there is one detail that quietly does a lot of heavy lifting: the hobby shop.

It shows up early. It sticks around. And it is never treated like a toy store. It feels closer to a garage for racers or a tuning shop for street bikes. Parts everywhere. Tools lying around. Bladers hanging out, talking shop, fixing things, upgrading, arguing about combos.

Takara wanted this to translate to the real world, where hobby shops will meet bladers’ needs for customization, parts replacement, repairs, etc. But we never really got to that point. Mostly, we just buy Beys or boosters and mix-and-match between those, with no real need for a dedicated hobby shop.

But the idea itself is quite cool. A dedicated, physical hobby shop to aid bladers. Buying parts in cheap. Testing customizations in a stadium in the back of such a shop. This is the level of reach Beyblade always wanted to have—but sadly, it couldn’t reach that.

Beyblade Was Pitched as a Serious Hobby, Not a Toy

Takara could have framed Beyblade as a simple “buy it, launch it, done” product. Instead, the anime keeps reinforcing a different idea: Beyblading is technical. Modular. Skill-driven. And deeply personal.

Your Bey is your machine.

The hobby shop exists to sell that fantasy. It normalizes a few important ideas:

- Beyblades break

- Parts wear out

- Customization is expected and even necessary

- Repair is part of the game

- Knowledge matters as much as genius, talent, or even the spirits (bit beasts in this example)

This is very different from how most toy lines are portrayed. In Beyblade, maintaining your top is almost as important as battling with it.

Customization was the Core Fantasy

There is just something about a hobby shop that grips you. No matter whom you liked or hated in Bakuten Shoot Beyblade, you had a distinct respect for the guys running the hobby shop (initially only Max’s father).

In fact, that name has caught on. We even have a well-known Beyblade seller/reseller here in India called the World Hobby Shop! (P.S.: His prices are very reasonable, and he restocks original Beys quite regularly).

Every time a blader walks into that shop, the message is clear: stock combos are just the beginning.

Attack rings, weight discs, bit chips, blade bases, cores, etc. The anime treats these like performance parts. Swap one thing, change behaviour. Mess it up, lose a match.

That framing is powerful.

It tells kids (and honestly, adults too) that winning is not just luck. It is tuning. Experimentation. Trial and error. The hobby shop becomes a place of learning, not consumption.

That is a very “advanced hobby” mindset.

The Shop as a Community Hub

Notice something else. The shop is never empty.

People hang around. They talk. They test Beys. They watch battles. It feels like a local scene, not a retail counter. That matters because Takara was not just selling tops. They were selling a culture.

A place where bladers belong.

This mirrors real-world hobby ecosystems perfectly. Think RC cars, model kits, trading cards, even cycling. The shop is not just where you buy parts. It is where knowledge spreads and identities form.

Takara clearly wanted Beyblade to sit in that same mental category.

In fact, I’d go as far as to say that the hoppy shop in Takara’s original Beyblade world is as critical as stadiums where all the tournaments take place.

There was a post on the WBO forum back in 2021 asking if any “brick-and-mortar crazy house sells a niche version of already niche toys”. The #1 argument against why that is not the case was that it’s going to be impossibly difficult to compete against Takara itself when it comes to selling Beys and parts. It won’t be official. But if Takara itself took it upon itself?

Who knows.

A Very Intentional Real-World Nudge

Let us be honest. Takara absolutely hoped this would spill into reality.

Anime-driven merchandising has always worked like this: show the behaviour, normalise it, then let demand follow. Hobby shops full of parts were not just worldbuilding. They were a business aspiration.

And for a while, it worked.

During the plastic gen and early Metal Fight era, part-buying, swapping, repairing, and modding were very real activities. Bladers cared about wear. They debated parts. They customized. The anime had primed them to do exactly that.

What We Lost Over Time

As generations progressed, something shifted.

Burst leaned harder into gimmicks and sealed systems. Repair became less visible. Customization narrowed. The idea of a “shop full of parts” slowly faded from both anime and reality. By the time Beyblade X came, it was much easier to just buy more boosters and test competitive combos than to have a hobby shop at all.

That early philosophy, though, still resonates. You can see it every time someone talks about tuning combos, weight distribution, or durability. That mindset was planted right at the start.

By that little hobby shop.

Why It Still Matters Today

That original message is why modern interest in metal builds, heavy parts, and repair-friendly designs makes sense. People are subconsciously returning to the first promise Beyblade made.

That this is not disposable plastic.

That it is a mechanical hobby. One where parts matter, upgrades matter, and the feel in your hand matters. The anime told us this from day one. We just did not realise how intentional it was at the time.

Takara was not just selling Beyblades.

They were selling the idea that somewhere out there, there is a shop full of parts, tools, and bladers like you. And if you care enough, you belong there.